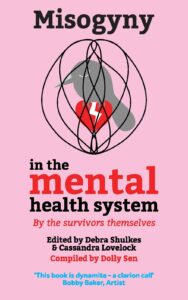

Misogyny Book Reviews

If you have ever used mental health services, especially if you are a woman or non-binary person, there are endless reasons not to talk about it. We are ashamed. We are afraid of the consequences, we don’t want to make a fuss. We are too tired, too sad, too happy. Too busy working or surviving or raising kids. We think we are somehow to blame. No-one listens to a mad woman. We don’t ever want to think about it, ever again.

Maya Angelou says “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you” – and she should know. But telling your story can also cause pain. We have to fight for a platform. We are often judged, dismissed or disbelieved. Talking from experience may mean that you are always defined or lessened by those experiences, potentially for the rest of your life.

The writers in this book took that risk. And the result is epic; a work of groundbreaking power and scope. It holds waiting lists and waiting rooms, outreach teams and GPs and locked wards and sections, counsellors and day centres and emergency departments; anxiety, parenthood, psychosis. From this breadth of experience, common themes emerge. The powerlessness and voicelessness of the patient; the lack of appropriate support; the damaging impact of psychiatric diagnosis – especially the gendered and damning diagnosis of Borderline/ Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder; the impact of gendered violence; the lack of recognition of neurodivergence in people assigned female at birth; fear and abuse on the wards including the violence of physical restraint.

Every story is different and particular. But as with all heartfelt writing, there’s a universality to it. If anyone wants to understand me and my years as a troubled teenager in 1980’s Burnley, or a psychiatric inpatient in 1990’s Liverpool, or my work with services across the UK in 2022 – they could read this book. It also includes experiences of exceptional care beautifully captured in Lottie McCartney’s illustration of “helpful things mental health professionals have – “you are worthy of care”, “I hear you”. Exceptional, because otherwise this is a story of services which have been failing for years – told by people who live that story.

“Having mental health lived experience filtered by mental health professionals is like lions representing bird song in roars”, reads Dolly Sen’s introduction. As a radical artist and educator, Dolly works in visual art, poetry and essays, film and sound. Small wonder then that the book encompasses a range of forms and voices. And though I am much more used to the standardised anthology with its house style, the democracy of form, style and tone found in this book is not just politically appropriate – it’s also one of its many strengths. With its movement between deeply personal testimony, drawings and handwriting, formal treatise, photographs, dialogue, memoir and graphic art, with its range of voices from formal to colloquial, the book is a crowded room, humming with conversation and song. Women and non-binary people speak directly to me – from a lectern, and a stage, from a phone, bearing the name of a friend. They are stood next to me at the bus stop, in a bar. They are real and various, alive.

That life is vital. As Dolly says ”the representation of mental health in patient notes does not give a person the essence of their life or their right to beauty”. And despite the pain in this book, there is joy – what Alexandra Pullen describes as “the reality, pain, normalcy and great beauty of our strange capable minds”. In the final essay, Bryony Ball critiques services for survivors of sexual abuse and violence, which are too often delivered by people who do not identify as survivors. As she browses the images on their websites and wonders if she too should be weeping by a rain-streaked window, Bryony reclaims her complex story with its mixture of trauma and pain, joy, desire and humour – and in doing so, she creates a space for all of our complex lives.

As do all of the writers in this book. Like G Gillet, who explains “I want to show you, the reader the complexities of trauma and mental illness” as she tells us about the serenity she finds in nature and art (and velour blankets from Primark!) in the middle of terror and pain. Or from Poppy Hugo, proclaiming “I am resisting and rejecting the narrative that mental health services imposed on my story. This is my story, my words.” In speaking authentically, the book perfectly negotiates the invisible line between art and action. As Jay Watts puts it in a defiant foreword: “Material reality – money to live and a kind benefits system, safe streets, decent housing – is central to what we fight for … Stories matter too. Stories can squeeze and suffocate us. But they also help us survive if we can claw our way to a space where we can write them, sing them, photograph them, dance them, at which point they become something different”.

This collection provides that space. Together, these stories are call to arms, where arms are weapons, where arms can defend us, where arms can keep us from drowning. Where arms can change the world. Where arms can hold us. Thank you for the gift of this book.

Fiercely brave and compelling testimonies that bear witness to appalling, gendered forms of discrimination in the system. These testimonies must be heard and put to good use, before progress towards a fair and just mental health system is possible. A system based upon an awareness of what’s happened to people, their living, social context is needed and these powerful narratives provide every clue as to how states of powerlessness and distress can be transformed into modes of empowerment and reclamation.

Professor Paula Reavey, Professor of Psychology and Mental Health, South Bank University

A book about women’s accounts of the services they have received (or not) to support their mental health should not read like this one – in a barely acceptable world never mind an ideal one. The overall sense one gets from reading these accounts is the fight which is needed, in the first instance to protect oneself from poor practice, and then to get any semblance of supportive services. The narratives are one of reversed expectations, services which should hear, mishear or are deaf, patients centred planning becomes patient centred blaming, therapeutic practices are anti-therapeutic and being treated becomes mistreated. Each story the authors tell provide rich contexts to their individual journeys, but the themes transecting all of them are clear. Mental Health professional practice dominates and dictates these life stories, throwing the cloaks of diagnostic taxonomies, services structures, and financial restriction around them until this is all that is seen and the woman is lost within, her voice and identity muted. Within this book these women unpeel layer by layer what the impact of these systems have been, revealing the very human needs, feelings and emotions arising from primary traumas of distressing early experiences and the secondary consequences of uncaring and insensitive services. One author captures this endeavour perfectly by describing the aim of her contribution as ‘writing yourself into existence, so I can say I am here’.

There are many lessons to be learnt from reading this book by people working in such services. The accounts several authors give about how being compulsory medicated cannot but be experienced as re-traumatising by victims or rape of sexual abuse is visceral. Likewise, the consequences of having labels attached such as Borderline Personality Disorder, which changes the women’s identity both to the perceived and perceiver, negating the woman before and now retelling her within this fiction of medical diagnosis. However, this is not a negative book, it is a call to arms, the energy to continue this fight is palpable. Neither is it a compilation of recovery stories, real life is messy, there are no clean stories of A to B, become unwell, get treated, become well and live happy ever after. There are stories of how women despite all odds have survived, had children, had and have careers and jobs, relationships and safe places to call home. These narratives provide rich picking for those willing to hear about how we can do better. Take the diagnostic, medicalised filters off and start by listening, what you hear may not need a diagnosis but what will be asked of you is humanity and respect.

Prof Jan Burns, Emeritus Professor of Clinical Psychology

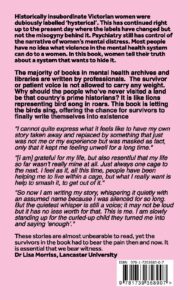

All of us working in mental health need to read these haunting, harrowing, and heartbreaking stories. This cannot continue. These stories are almost unbearable to read, yet the survivors in the book had to bear the pain then and now. It is essential that we bear witness.

Dr Lisa Morriss, Lancaster University

This book is dynamite – and a clarion call to people with the power to make changes to our mental health services – which are currently, persistently, failing to support women in distress.

It’s packed full of important testimonies from women of the treatment they received from these services – which are neglectful and bungling at best, but often cruel and abusive in extremes.

There’s the brilliantly inspiring writing of Dolly Sen, accounts of gifted and compassionate mental health staff, and tales of recovery – but it’s frequently an extremely harrowing read as well.

Writers describe a mental health system still fundamentally based on a patriarchal understanding of women. Psychiatry has picked up the baton – from labelling women as ‘witches’ to its contemporary form – ‘borderline personality disorder’.

This fate befell me during a period of my life when I experienced such extreme anguish that I struggled to survive. But I did and, with the right help and my own efforts, my life, work and relationships flourish. Yet that outrageous, gaslighting label will sully my medical history till I die and my outrage at the injustice I witnessed in services for women deeply troubles my soul.

How long must we wait for society at large to shudder in shame – as it now does by psychiatry classifying homosexuality as a mental disorder as recently as the 1960s – at the gaslighting of victims of childhood sexual abuse, or women traumatised by early troubled family lives? How long will neurodivergent women be victimised by the mental health system?

This important book is vital in helping to bring about that change – by contributing these women’s voices to the public realm.

So pick it up and read what you can!